2025 | Volume 26 | Issue 5

Author: Associate Professor Victor Kong, MD, PhD, ChM, MSc, DRCPSC, MRCS, FRACS, Trauma surgeon, Auckland City Hospital

It is 0600, the sky is clear, and the birds are chirping. It is summertime in Johannesburg. I get into my Suzuki hatchback to drive the same route to the hospital as I do every day and begin to reflect on the incredible journey my trauma surgery training has taken me on.

Looking back to this time now, I realise I have lived in seven countries, worked in different healthcare systems, and have met many people (patients, friends and colleagues alike) from vastly different cultures. All this has taught me much and has undoubtedly shaped me as a trauma surgeon. When working at Bara, I realised I had achieved my dream of becoming a truly ‘international’ surgeon. Many doctors (not just surgeons) from every continent come to Bara every year to train and work in trauma surgery. The incredible volume of trauma cases, the high quality of trauma care offered, and the excellent training received, are some of the reasons why it is such a desirable place to work. South Africa has always been a place that offers much to a clinician, and gaining clinical experience in trauma surgery is no exception.

In fact, after conducting a study of international doctors who had trained in countries considered relatively ‘peaceful’—and after spending time training in South Africa—I discovered a striking disparity. To gain equivalent experience in managing penetrating injuries, those doctors would have needed more than 100 years of training in their home countries, and more than 200 years for gunshot wounds alone. It was a small study, but I do believe the message was fairly clear —South Africa is undoubtedly the mecca of trauma surgery training. For some, the experience would be more than what many would see in their entire career—many times over. Therefore, although the trauma in South Africa is deemed a ‘malignant epidemic’, the by-product of this is that trauma surgeons who train and work in South Africa amass a wealth of experience and contribute significantly to the knowledge pool in the field.

When I was on call, I often said in jest that it feels as if the whole of the United Nations is present. Doctors work alongside well trained and incredibly hard-working South African colleagues, who have much to teach. In my experience, I could be working with a surgeon from Sweden, an emergency physician from Italy, and an anaesthetist from Spain. All have been at Bara, and all want to be at Bara, in the centre of the action and learning, and to experience what no training books, courses or simulation can offer—real trauma. Even now, the more I learn, the more I want to learn—the learning never stops.

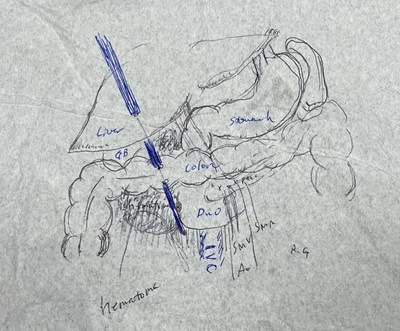

On one rather memorable evening, when a colleague from Japan, Dr Riki Ganeko and I were reflecting on a challenging case, I was astonished to discover that he could draw accurate sketches of operative findings, as in what one sees in an operative atlas. He did this on a piece of tissue paper in the doctor’s tearoom.

Dr Riki Ganeko, Dr Yuma Iba and myself in the doctor’s tearoom

Sketch from an operation (with permission from Dr Riki Ganeko)

The work at Bara is challenging, the hours are long, and like many healthcare settings, the system is far from perfect. I was fortunate enough to share a house with two surgeons from Japan who came to Bara for their trauma training, and we would often exchange ideas, knowledge and experiences. More generally, exchanging knowledge with colleagues from all over the world opened my eyes, giving me a deeper appreciation of my current work in New Zealand.

Dr Yuma Takeuchi, myself and Dr Riki Ganeko at the hospital entrance

One of the most important philosophical concepts I learned from my Japanese colleagues is of Wabi-Sabi. It is a Japanese concept, which teaches an appreciation of the imperfect, rather than looking to find fault in imperfections; it can be acknowledged that even imperfect things can be perfect in their own way. In many ways, every trauma system has its flaws, and my own experiences over the years—spanning from working in the UK, Ireland, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa—have convinced me that the perfect trauma system does not exist. However, Wabi-Sabi does not imply that one should not move forward to improve and strengthen. I have found solace in the idea of Wabi-Sabi because it allows me to appreciate the strength of each healthcare system I encounter. The system at Bara was far from perfect, but this is also the case with other healthcare systems, which can be challenging in their own ways, and some more than others. Reflecting on this encourages me to continue to strive towards greater heights for the benefit of trauma patients, and to continue to pursue this course as my life long career.

As I was driving home in my Suzuki hatchback from my long shift, I saw the beautiful sunrise of Johannesburg, signalling that a new day had begun. I was mesmerised by the innumerable jacaranda trees dotted throughout the suburbs, and the light purple petals of these trees, which covered the walkways. Growing up, I learned that jacarandas represent beauty, resilience, and renewal. This seemed an apt scene as I reflected on the last 24 hours of my work. The concept of Wabi-Sabi has now slowly become part of how I see things, both professionally and personally.

Jacaranda trees on the walkways of Johannesburg