2025 | Volume 26 | Issue 6

Dr Glen Farrow OAM FRACS

I was trying to stuff a parachute into its canvas bag after landing on a windy drop zone near Nowra. It was like wrestling an octopus in a wind tunnel—stuff one corner in and the others took off again. A nearby Company Sergeant Major (CSM) gave me words of encouragement. “Come on Doc, I hope you can stuff my guts back better than that on a battlefield.”

Years later, I could almost hear that same CSM chuckling behind me as I tried to close a three-year-old with abdominal compartment syndrome. Thankfully, having a silo up my sleeve proved useful.

The same CSM would always reassure us.

“Cheer up, it’s safer jumping out of an aircraft than actually landing in one!”

We all laughed (nervously).

“Nah, must be joking.”

The evidence base for parachuting is shaky. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials by Smith and Pell in 2008i concluded, ‘as with many interventions intended to prevent ill health, the effectiveness of parachutes has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation by using randomised controlled trials.’ They recommended a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover trial, ideally using the most vocal evidence-based medicine advocates as volunteers.

So, how safe is parachuting compared to landing in the aircraft?

The answer it seems is, ‘it depends’.

Commercial airline travelii is of course far safer than recreational parachutingiii, but military aviation is a different story. The average fatality rate from flying in a C130 is 3.3 per 100,000 flying hoursiv. While military parachuting has relatively high rates of injury and death , with an average sortie lasting about three hours that’s roughly 9.9 deaths per 100,000 sorties (jumps)—10 times higher than the risk of death from jumping itself. As usual the CSM was right.

Comparing parachuting with commercial flying isn’t the most shocking comparison. Indeed, the unexpected inpatient injury rate—about 10%vii, dwarfs most military risks. The unexpected death rate, up to 30 per 100,000viii, is equally sobering. Critics will say that inpatients are already sick and more likely to die, but hospital safety data only includes unexpected injury and potentially preventable death, not all complications and deaths.

When an activity that looks dangerous is actually safe, but an activity that should be safe is dangerous, we must ask why.

The reason is simple: paratroopers are trained relentlessly because their lives depend on it. Doctors, despite the stakes, are not trained that way.

*Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition

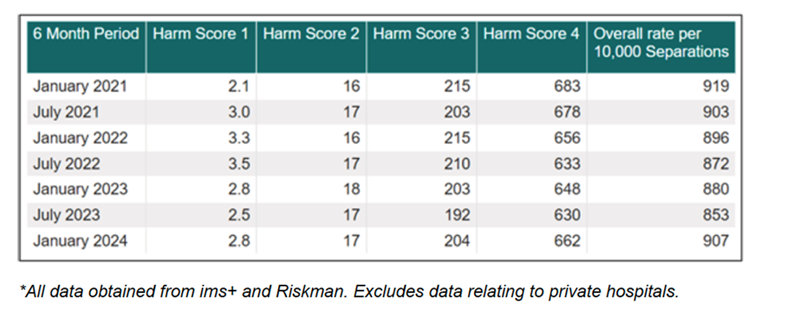

Table 2 shows us exactly where things fail: recognising deterioration and responding appropriately. In addition, root cause analyses (RCA) are kept confidential, no lessons are learnt and the doctor concerned often doesn’t know the outcome. There is no accountability. As a result, serious potentially preventable adverse events continue to occur at unacceptable rates in our hospitals.

Table 3: Incidents in NSW Public Hospitalsix

RACS has developed the CCIrSPx course for Trainees but until the entire medical profession teaches patient safety explicitly to all undergraduates and junior doctors, our performance in safety will continue to stagnate.

You may have noticed that its statistically more dangerous to stay at home, go to work, or even play golf than fly on a commercial airliner. This is as good an excuse as any to take a holiday this Xmas for your own safety.

Even the claim “evidence shows I’ll be much safer taking three months study leave flying around Europe than staying home” might work.

As for me, no amount of evidence will get me jumping out of a plane again, unless of course my life depends on it.

i “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials” Gordon C S Smith, Jill P Pell BMJ 2003;327:1459–61

ii Flight Safety Foundation https://flightsafety.org/asw-article/icao-data-show-declining-accident-rates/ Accessed 12 November 2025

iii United States Parachute Association (USPA) https://www.uspa.org/Discover/FAQs/Safety Accessed 12 November 2025

iv C130 Flight Mishaps https://www.safety.af.mil/Portals/71/documents/Aviation/Aircraft%20Statistics/C-130FY23.pdf accessed 12 November 2025

v Military Static Line Parachute Injuries Farrow GB Aust N Z J Surg 1992;62(3):209-14

vi U.S. Army parachute mishap fatalities: 2010–2015. Johnson ES, Gaydos SJ, Pavelites JJ, Kotwal RS, Houk JE. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2019; 90(7):637–642.

vii Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS (Institute of Medicine) To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000

viii Charting the Quality and Safety of Healthcare in Australia: 2004, Chapter 4, p 70, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/chartbk.pdf accessed 14 November 2025

ix Patient Related Incident Data, Clinical Excellence Commission NSW, https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/about-the-cec/reports-and-publications/Biannual-Incident-Report/patient-related-incident-data accessed 15 November 2025.

x Care of the Critically Ill Surgical Patientâ (CCIrSP) Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.